The other day I was reading a random article while doing some research on female insane asylums in the Victorian era. One article lead to another, and before I knew what I was doing, I was reading a long, drawn out research paper about Female Hysteria and the history of the vibrator.

I debated a bit about whether or not to write an article about such a thing, and then I decided to go ahead and do it. The history of the vibrator was absolutely nothing like what I expected it to be (And really, who expects it to be anything? Who even thinks about this stuff?) and it was far more interesting than I anticipated, so here we are.

This article is long, and there are a lot of twists and turns, so stick it out, reader. You'll be glad you did. This doesn't go where you expect it to go.

Are you ready?

Buckle up.

|

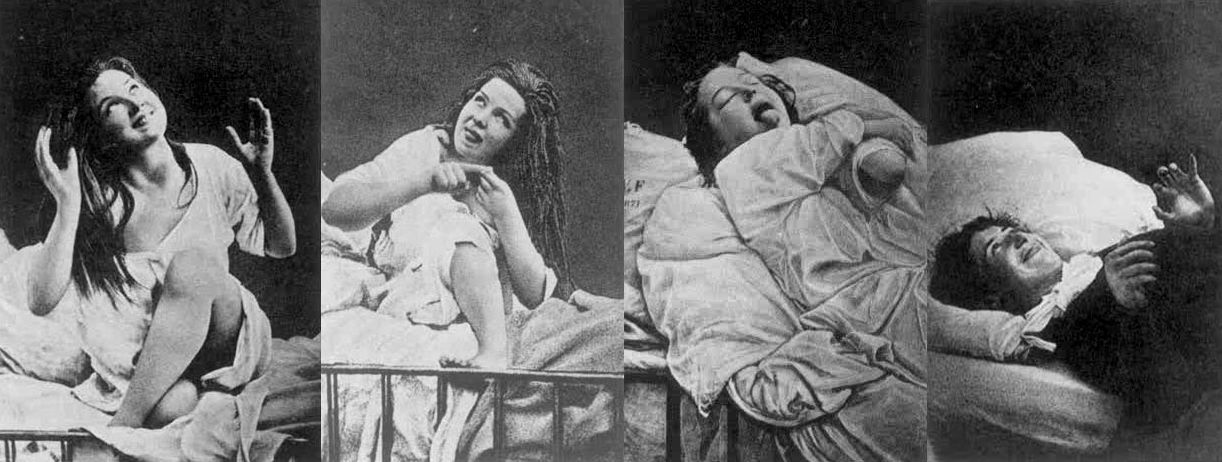

| Image from Wikipedia |

Female Hysteria in the Victorian Era

Humanity has a long, complicated history of diagnosing women with "hysteria". For a long time, the term served as a sort of catch-all for anything that was wrong with women. In the Victorian era, the woman was a focus of purity. She was a wife, a mother, and a support system for her husband, but in all things, she was a pretty stationary force with a lot of internalized and societal pressure heaped on her shoulders. It's not easy to be a beacon of purity in an impure world.

With the rigid divides of society between men and women, men were often the ones who got to move around, while women stayed at home, under the thumb of those around them. The common belief that women were more emotional, weaker, more dependent, needed to be guided made women more susceptible, so it was believed, to illness, both mental and physical. This belief of increased susceptibility to disease lead to many women being diagnosed with insanity, or Female Hysteria and it's related conditions.

"On the basis of Victorian gender distinctions, it was common for female patients to be diagnosed as suffering from hysteria. In the 19th century upper and middle class women were completely dependent on their husbands and fathers, and their lives revolved around their role as resistible daughter, housewife, and mother. With so little power, control, and independence, depression, anxiety, and stress were common among Victorian women struggling to cope with a static existence under the thumb of strict gender ideals and uneylding patriarchy.

"Characterized by nervous, eccentric, and erratic behavior, the epidemiology of hysteria eluded medical explanation in the Victorian era. Although there were hysterical males, attributing the condition to the female nature fit the social model of women and validated the medical integrity of psychiatry by providing a suitable diagnosis. For hysterical women and their families, the asylum offered a convenient and socially acceptable excuse for inappropriate and potentially scandalous behavior. Rather than being viewed as bad and immoral women, honour and reputation could be maintained by the diagnosis of a medical condition and commitment to an asylum." (The Hysterical Female)

Around the mid-1800s, people began studying the condition of female hysteria. One Silas Weir Mitchell, an American physician, promoted a "rest cure" for the condition, declaring that women who were hysterical needed rest, and no exposure to physical or mental activities. However, the men who were prescribed with this condition were advised to engaged in a lot of rigorous outdoor activity.

According to Medical News Today, "Mitchell famously prescribed the rest cure to the American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who found the experience so harrowing that she wrote "The Yellow Wallpaper," a psychological horror story that maps the slow psychological deterioration of a woman who is forced by her doctor, her husband, and her brother to follow the 'treatment'."

That same article goes on to discuss the ideas of a few other leading theorists of the times. Freud had several ideas about female hysteria over the years, yet it seems he believed the psychological symptoms of female hysteria were a result of erotic suppression. One French neuropsychiatrist named Pierre Janet believed "hysteria came from a persons warped idea of physical illness."

The interesting thing to note here, is that female hysteria was widely known about, and trips to the asylum for embarrassing female relatives happened. No one really seemed to address the mental health component for all of this, or address the social and familial pressure many women were buckling under, or the weight of the life they were living. Rather, it seems it was an era where embarrassing women were quickly diagnosed and dealt with by important men who had many likewise important theories.

|

| Image from Wikipedia |

Around the mid-century, other theories about what hysteria is came into the conversation. "Jean-Martin Charcot argued that hysteria derived from a neurological disorder and showed that it was more common in men than women. Charcot's theories of hysteria being a physical affliction of the mind and not of the body led to a more scientific and analytical approach to hysteria in the 19th century. He dispelled the beliefs that hysteria had anything to do with the supernatural and attempted to define it medically... Though older ideas persisted during this era, over time female hysteria began to be thought of less as a physical ailment and more a psychological one." (Wikipedia)

George Beard, a physician catalogued seventy-five pages of symptoms and signs of hysteria, eventually concluding that almost anything could lead to a hysteria diagnoses.

"Physicians thought that the stress associated with the typical female life at the time cause civilized women to be both more susceptible to nervous disorders and to develop faulty reproductive tracts. One American physician expressed pleasure in the fact that the country was "catching up" to Europe in the prevalence of hysteria." (wikipedia)

There were numerous ways to deal with female hysteria. Some doctors in the 1800s determined that female hysteria and insanity was a disorder that came from the genitals, and so numerous doctors decided the best way to cure hysteria and insanity was to perform hysterectomies, or extremely invasive surgeries where the woman's uterus would be removed, thus removing her mental illness.

This belief that female insanity spawned from female genetalia was extremely convenient, and was no small part of why mental health was so stigmatized and sexualized for so long, and I'd argue, still is to one extent or another today.

How all of this ties to vibrators

With so much of hysteria being tied to the female condition, even female genitalia, it is no wonder someone took the leap and connected the treatment of the condition to something like a vibrator.

In 1999, Rachel Maines wrote a book called The Technology of Orgasm, which claimed vibrators were created to treat female hysteria. In the book, she argued that clitoral massage was used throughout history to treat this condition, and that orgasms, or "paroxysm" were understood as a way to treat female hysteria. The paper, as it turned out, made some pretty big waves, and it is a fun story. Imagine these doctors, so tired after a day of massaging hysterical women, their hands cramping, and realizing they needed help so they put their big brains together and created vibrators, so women could cure their own hysteria and doctors wouldn't have to suffer that terrible hand cramping anymore.

Except, after the book was released, some scholars got together and started really looking at what Maines said, and studying her sources for her claims and they found holes. Lots and lots of holes.

According to The Atlantic, "But that's just not true, according to Lieberman and Eric Schatzberg, the chair of the School of History and Sociology at Georgia Tech. There is scant evidence that orgasms were widely understood as a cure for female hysteria, and there's even less evidence that Victorians used vibrators to induce orgasm as a medical technique, they say. "Maines failed to cite a single source that openly describes use of the vibrator to massage the clitoral area," their paper says. "None of her English-language sources even mentions production of 'paroxysms' by massage or anything else that could remotely suggest an orgasm." (The Atlantic)

"Even though Maines now calls her argument a "hypothesis," her writing in The Technology of Orgasms does not take the same provisional tone. "In the Western medical tradition, genital massage to orgasm by a physician or a midwife was a standard treatment for hysteria," she wrote in that book's first pages. "When the vibrator emerged as an electromechanical medical instrument at the end of the 19th century, it evolved from previous massage technologies in response to demand from physicians for more rapid and efficient physical therapies, particularly for hysteria." (The Atlantic)

The article goes on to discuss more of Maines's claims, and then rebuts them from a more scholarly point of view. The point remains, however, that Maines released a book of claims, and they were fun claims that filled the public consciousness with certain quaint ideas, and they took off. It seems, the more I research, the more Maines's claims about vibrators being developed to treat female hysteria via orgasm have been widely rebuffed and soundly decried as unsubstantiated.

So, where did vibrators really come from?

The Real Deal

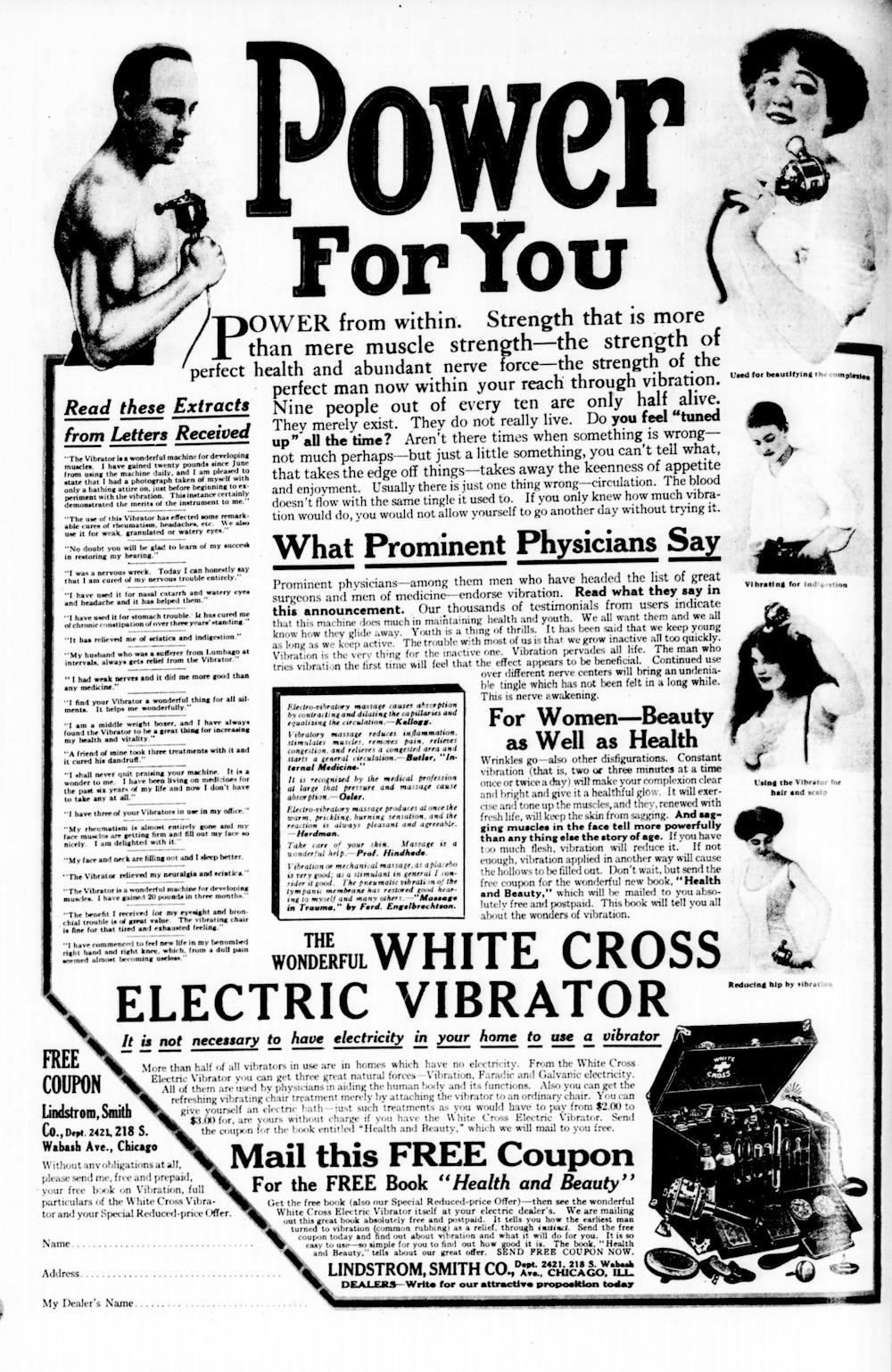

|

| From The Conversation |

Comments

Post a Comment