Folks, I've got COVID and it's really nailing me to the wall right now. I keep trying to be productive and get work done, but my mind is having a hell of a time staying focused. I've been, instead, been sort of listlessly engaging my brain bag in whatever way it is currently up to being engaged. So, me being me, I've been listening to this podcast about Jack the Ripper. Today, while I was listening to an episode, I went online and looked up victim photographs. There's one victim photograph of the fifth victim which has been colorized and slapped on a historical colorized photo subreddit. (You can see it if you click here, but be warned, it's extremely graphic and if you have a low threshold for nasty, maybe skip over it and stay with the black and white version you've probably already seen.)

Anyway, it was in said subreddit where I saw someone say, "If you think Jack the Ripper was bad, look up Gilles de Rais" and I perked up because I've never heard of this guy before.

Off to Google I went. I'm currently waiting for a medication dose to kick in so I can hopefully think enough to get some work done, and while I wait, I figure I'll tell you a bit about one Gilles de Rais. Trigger warning: This involves a serial killer and children. I try not to go into too much detail, but it's horrible however you look at it, so please go forward with caution.

As always, additional reading will be linked at the end of the post.

So, who is Gilles de Rais?

|

| Gilles de Rais, image from Britannica (link at the end of the post). |

Gilles de Rais lived from 1404-1440 in Brittany. Living as a nobleman in contested territory during the Hundred Years' War, he was blessed with having an impetuous and hot-headed temperament, both good qualities in a soldier. However, Gilles's life was beset by tragedy. Around the year 1415, his father Guy de Lavel died from a hunting accident, and his mother, Marie de Craon, died from unknown causes shortly after. Gilles (and his younger brother) was sent to his maternal grandfather, Jean de Craon, to raise. Jean de Craon set out to advance his grandson's fortunes through marriage and military engagements, and he succeeded on both accounts.

"Craon was a schemer who attempted to arrange the marriage of twelve-year-old Gilles to four-year-old Jeanne Paynel, one of the richest heiresses in Normandy; when the plan failed, he attempted unsuccesfully to unite the boy with Béatrice de Rohan, the niece to the Duke of Brittany.

On 30 November, 1420, Craon did substantially increase his grandson's fortune by marrying him to Catherine de Thouars of Brittany, heiress of La Vendée and Poitou. Their only child, Marie, was born in 1433 or 1434." (Wikipedia)

Gilles was said to be a skilled and fearless fighter, which was important in the area where he lived, as he was beset by war on all sides. In 1429, the dauphin (later known as Charles VII) ordered Gilles to protect Joan of Arc on the battlefield, and that is exactly what Gilles de Rais did. Rising to the occasion, he fought alongside Joan of Arc through numerous battles, keeping her safe all the while. This, of course, made Gilles infamous.

According to Britannica, "The two fought together in some of the major battles of her short career, including the lifting of the Siege of Orléans. In 1429 he was appointed to the position of marshal of France—France's highest military distinction."

Joan, however, was burned to death in 1431 and from that point on, Gilles spent more time at his estates. At the time, he had plenty of boltholes to choose from thanks to the loveless marriage his grandfather arranged for him with the wealthy heiress, Catherin de Thouars. However, Gilles had a taste for the high life and didn't have the funds to afford said life, so he started burning through his grandfather's carefully amassed fortune, and then set about selling off family land to fund his lifestyle when he could no longer dip into his family's coffers. As you can imagine, people weren't too thrilled about that. They got madder and madder and Gilles kept on keeping on. He lived lavish and pulled away from society, becoming almost a complete recluse by 1434-1435.

"In either 1434 or 1435, Rais gradually withdrew from military and public life to pursue his own interests: the construction of a splendid Chapel of the Holy Innocents (where he officiated in robes of his own design), and the production of a theatrical special, Le Mystère du Siège d'Orlèans. The play consisted of more than 20,000 lines of verse, requiring 140 speaking parts and 500 extras. Rais was almost bankrupt at the time of the production and began selling property as early as 1432 to support his extravagant lifestyle. By March 1433, he had sold all his estates in Poitou (except his wife's) and all his property in Maine. Only two castles in Anjou, Champtocé-sur-Loire and Ingrandes, remained in his possession. Half the total sales and mortgages was spent on the production of his play. It was first performed in Orléans on 8 May 1435. Six hundred costumes were constructed, worn once, discarded, and constructed afresh for subsequent performances. Unlimited supplies of food and drink were made available to spectators at Rais's expense." (Wikipedia)

In 1435, several parties appealed to the Pope in an attempt to disavow the Church of the Holy Innocents (he refused). Then they appealed to the king, who decried Gilles as a spendthrift and forbid him from selling more of his or his family's property, and no subject of the king was allowed to enter into business with him. He ended up chased out of Orleans by creditors, and was going even more in debt to pay them off, using family heirlooms, precious jewels, clothes, and books as collateral. However, the king's edict didn't extend to Brittany, and so he ended up going home, safely tucked away from the King of France and his debt collectors.

In 1438, Gilles discovered he had a unique interest in the occult and alchemy, and decided it was time to press right into that particular niche and that's exactly what he did. "According to later testimony from members of the clergy, Rais had previously sought assistance in summoning a demon to his castle. He is said to have reached out to Francois Prelati of Florence, who told him that the demon required an offering of "parts of a child" provided in a glass vessel. Yet it seems no demon ever manifested in the castle." (The Archive)

My guess is the demon not manifesting on the first try probably just gave him justification to keep going. If the demon doesn't arrive after one child, maybe it will after five. And once you get a taste for it, if you're a person with these inclinations, that's probably all the justification you ever need to try, try again. Or, maybe it had nothing to do with this. The drive could have always been there, this priest perhaps just gave him a reason to feel better about the action. Who knows. The dead don't tell their secrets.

Soon, people who lived around Gilles started noticing children disappearing and rumors began to spread. However, Gilles was basically untouchable. Despite the disfavor he'd fallen to with the King of France, in Brittany, he was under the protection of higher authorities (the Duke of Brittany was protecting him), and so no one came calling when children disappeared. No one asked questions. No one dared say a word.

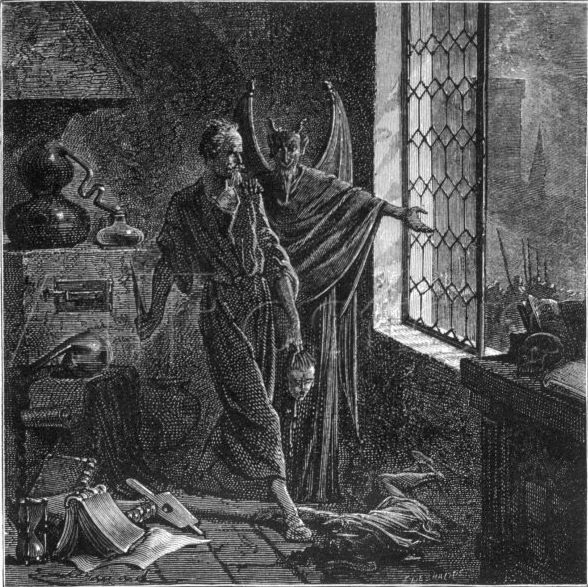

|

| An Illustration of Gilles de Rais, Baron de Retz from L'Histoire de la magic, 1870. (From Atlas Obscure) |

The most common estimates I see are that Gilles possibly killed between 100-200 children, though some estimates range as high as 600 (I have a really hard time believing that number).

Gilles later admitted to murdering children, and said he began doing so as early as the spring of 1432 or 1433. Rais claimed the first murders happened at Champtocé-sur-Loire, but no account survives. Rais then moved to Machecoul, where he killed (or ordered the death of) a large but unknown number of children after he sodomized them.

"The first documented case of child-snatching and murder concerned a 12-year-old boy called Jeudon (first name unknown), an appretice to the furrier Guillaume Hilairet. Rais' cousins Gilles de Sillé and Roger de Briqueville asked the furrier to lend them the boy to take a message to Machecoul, and when Jeudon did not return, the two noblemen told the inquiring furrier that they were ignorant of the boy's whereabouts and suggested he had been carried off by thieves at Tiffauges to be made into a page. At Rais' trial, the events were attested to by Hilairet and his wife, the boy's father Jean Jeudon, and five others from Machecoul." (Wikipedia)

A further quote from a testimony at Gilles's trial (which I've seen all over the place, but I nabbed specifically from Wikipedia) says this, "[The boy] was pampered and dressed in better clothes than he had ever known. The evening began with a large meal and heavy drinking, particularly hippocras, which acted as a stimulant. The boy was then taken to an upper room to which only Gilles and his immediate circle were admitted. There he was confronted with the true nature of his situation. The shock thus produced on the boy was an initial source of pleasure for Gilles."

So, how did he get caught?

Well, Gilles, as it turns out, had a bit of an argument at church and ended up kidnapping a priest (the dispute was about some unknown issue, but it is not believed to have been related to the murders). Kidnapping is a bad idea, and kidnapping a priest in the 1400s was a particularly bad one, especially if the priest ends up surviving. The priest inconveniently escaped and ended up going to the officials about what happened. This prompted the Duke of Brittany, who had been protecting Gilles all this time, into action. Gilles and two of his bodyguards were arrested on September 15, 1440. A secular investigation was launched to corroborate the priest's story, and soon officials had enough witness testimony to believe they had enough evidence to convict Gilles and his bodyguards of murder, sodomy, and heresy.

Soon, people started coming forward to tell their own stories. Children would go to the castle to beg for food, only to never be seen again. Others were lured away on errands, like the first reported incident I mentioned earlier. Sometimes, if they just looked vulnerable, Rais's bodyguards (named Henriet and Poitou) would just grab them and go. There is a rumor (unsubstantiated, but I've seen it claimed a lot) that some of the testimony about these incidents were so graphic, they were stricken from the public record.

"Children had gone missing in the areas around de Rais's castles, and many of the disappearances seemed to be connected to the activities of de Rais and his servants. Because it was common for young boys to be permanently separated from their parents if they were taken on by nobles as servants or pages, some of his victims' parents would have been truly unaware of their children's fates. In other areas, though, de Rais's murerous predilections may have become something of an open secret—it came out during his trial, for instance, that witnesses had seen his servants disposing of the bodies of dozens of children at one of his castles in 1437—but the families of the victims were restrained by fear and low social status from taking action against him." (Britannica)

Gilles was given one last chance to confess, or be tortured to confession. On October 21, he surprised everyone by fully confessing to all crimes.

"Execution by hanging and burning was set for Wednesday, 26 October. At nine o'clock, Rais and his two accomplices proceeded to the place of execution on the Ice de Biesse. Rais is said to have addressed the crowd with contrite piety and exhorted Henriet and Poitou to die bravely and think only of salvation. His request to be the first to die had been granted the day before. At eleven o'clock, the brush at the platform was set afire and Rais was hanged. His body was cut down before being consumed by the flames and claimed by "four ladies of high rank" for burial. Henriet and Poitou were executed in similar fashion but their bodies were reduced to ashes in the flames and then scattered." (Wikipedia)

Oddly enough, Britannica mentions that the quiet piety with which Gilles approached death, "brought him posthumous acclaim as a model of Christian penitence. A three-day fast was even observed after his death. In one last nauseous irony, a tradition emerged in which parents around Nantes commemorated the anniversary of de Rais's execution by whipping their children, perhaps to impress upon them the gravity of the sins for which he had repented. This practice is believed to have survived for more than a century after his death."

Questions of Gilles's guilt have persisted to this day.

In 1992, another trial was performed, which turned into quite a media event. A team of lawyers, writers, former French ministers, parliament members, a biologist, and a medical doctor were assembled, and Gilles de Rais was found innocent of all charges. However, it was noted that no one ever asked a qualified medievalist to testify and the trial was largely considered a farce.

There are a few reasons people might not believe Gilles was actually guilty. Some people believe Gilles was actually a victim of a plot either by the French State or the Catholic Church, a plan for them to gain retribution by orchestrating Gilles's fall. Some believe he felt prey to the Inquisition. Some like to remind people that the Duke of Brittany gained all of Gilles's land and titles when he was convicted, and he liberally distributed them to his most faithful subjects. While Gilles had very little wealth to his name, he still sat on some nice land that a lot of people wanted. Others like to point out that Gilles only confessed under the threat of torture.

That being said, most historians still believe that Gilles de Rais was the serial killer that he claimed to be. Also, fun note: The story of Bluebeard was inspired by Gilles de Rais.

Further Reading:

Gilles de Rais: History's First Serial Killer? - Britannica

Gilles de rais, the Serial Killer Who Slaughtered 100 Children - All That's Interesting

French Knight Gilles de Rais Inspired the Folktale "Bluebeard"

The Modern Movement to Exonerate a Notorious Medieval Serial Killer - Atlas Obscura

Comments

Post a Comment